Politically exposed persons (PEPs) should always be on the compliance radar as a consequence of the elevated risk of financial crime that they present. However, recent events have seen PEPs take on new prominence, with revelations that a number of high profile individuals in the UK have had banking services denied, or their accounts closed, by the banking institutions they were using.

The closures drew media attention and sparked a public debate about what constitutes a PEP, how long that status applies, and how financial institutions deal with PEPs as customers. The resulting fall-out saw interventions by members of parliament and affected the financial institutions themselves, leading to the resignation of the CEO of one of the banks. As regulators around the world grapple with the PEP compliance question, let’s take a closer look at the current discussion surrounding the treatment of high risk individuals.

Understanding Politically Exposed Persons

A politically exposed person is an individual elected or appointed to a high profile political position, or employed in a similarly prominent public role. The term includes politicians, government officials and employees, members of the military, or high ranking members of international organisations.

PEPs pose a higher risk of financial crime because they often have access to sources of public funding, and may be able to avoid anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-financing of terrorism (CFT) controls. Their positions typically also make PEPs more vulnerable to bribery and corruption, or having sensitive information leveraged against them by criminals. Accordingly, firms must typically apply more intensive AML/CFT compliance measures to PEPs, including enhanced customer due diligence (EDD).

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) sets out three categories of PEPs, including, foreign, domestic, and international PEPs. It also assigns three levels of risk (high, medium, and low) depending on details of the individual PEP’s level of authority and influence. The FATF extends the term PEP to cover relatives and close associates (RCA), who pose a similar level of AML/CFT risk because of their proximity to PEPs.

As part of their risk-based AML processes, financial institutions are required to apply Know Your Customer (KYC) measures to PEPs to establish their AML risk – and then deploy appropriate compliance measures.

UK PEP Controversies

The way that banks and financial institutions deal with PEPs has become a topic of heated public debate in the UK after a number of prominent politicians and other public figures were refused banking and financial services. While the institutions argued that the closures were the result of regulatory or procedural necessity, the incidents prompted accusations that PEP regulations were being applied simply as a reaction against the customer’s PEP status, or even used to penalise certain political affiliations.

In July 2023, for example, UK Reform party-founder Nigel Farage alleged that Coutts bank, which is part of the Natwest group and specialises in high net worth individuals, had closed his personal and business accounts for political reasons – an act he characterised as “serious political persecution”. Current UK Chancellor Jeremy Hunt also revealed that he had been refused an account with digital bank Monzo in 2022 as a result of his PEP status.

RCA Issues

Any kind of PEP status that is applied to an individual can cause wider day-to-day issues, including for their families and other close associates. For example, following Nigel Farage’s complaint, Ivo Dawnay, brother-in-law of former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, revealed that he was blocked from using a currency exchange in Mexico as a result of his family connection. The UK’s Energy Security Secretary, Grant Shapps, also revealed his family had struggled with PEP-related issues. Shapps revealed that “every single member” of his close family had trouble opening accounts with banks, or were simply refused accounts, as a result of their RCA status.

Government Response to De-Banking Incidents

Despite the banks stating that they were following risk-based PEP regulations, the treatment of UK PEPs has prompted a governmental response. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak commented that individuals should not be “denied financial services because they’re exercising their lawful right to free speech”, while City Minister Andrew Griffith contacted the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), emphasising the importance of the proportionate application of PEP measures so that they do not “unduly burden or prevent democratically elected individuals, public officials, or their respective families from access to essential banking services”.

The government interventions accompanied emerging data that suggested UK high street banks are closing over 1000 accounts every day – with over 343,000 closed between 2021 and 2022. The de-banking of PEPs has also led to outcry from other customer groups: the Muslim Council of Britain, for example, recently argued that British Muslims are disproportionately affected by the “arbitrary closure” of accounts, and urged the government to launch a review.

In late July 2023, Nigel Farage revealed that Coutts had contacted him and offered to reinstate his personal and business accounts, but that he was also seeking compensation for the incident. Farage has also launched a website dedicated to addressing the “major scandal” of unfair account closures.

PEP Declassification Challenges

PEP screening measures are critical to effective AML/CFT compliance, however, part of the reason why the rules are so controversial is that, under the risk based approach, they are often applied after a PEP’s political role ends, or after they have left the position that conferred the level of criminal risk. For example, banks commonly continue to apply PEP status to former senior MPs (and their RCAs), potentially restricting access to financial products and services unfairly or inconsistently.

There is no universally-accepted time limit for declassifying a PEP, and what limits there are vary across jurisdictions. While some regulators assert that PEP classification should be applied for life under a “once a PEP, always a PEP” approach, others argue that customers can, and should, be declassified if certain conditions are met.

The FATF asserts that institutions may take an “open ended approach” to PEP declassification, but that the process “should be based on an assessment of risk and not on prescribed time limits”. However, most jurisdictions, including the US and the UK, impose a statutory limit of between 12 and 18 months for PEP declassification, and a requirement for an assessment of certain risk factors, including:

- The potential political influence that the customer could still exercise

- The level of seniority the customer had when they were in their political position or role

- How long the customer held their political role

- The link between the customer’s current job or function to their former political role

- The inherent level of corruption in the customer’s country of residence

- The customer’s financial behaviour and source of wealth since leaving their political role

- The quantity and content of adverse media published about the customer

Regardless of those risk factors and any discretionary allowance, it is critical that financial institutions understand, and follow, regulatory requirements for PEP declassification that apply within their jurisdiction. In the UK, for example, the FCA requires PEP status to apply “for a period of at least 12 months” after the customer leaves their political role.

FCA PEP Regulation Review

While the UK’s regulator imposes a minimum 12-month period on PEP classification, recent events have prompted calls for an official review of the rules. The UK government passed a bill to initiate the review, The Financial Services and Markets Act 2023, in June 2023.

In his 2023 communication to the FCA, Andrew Griffith stressed the need to strike a balance between AML/CFT compliance and customer PEP classification, treating domestic PEPs “in a manner which is in line with their risk” while not closing accounts “solely due to their status as a PEP”. In response to the high visibility of the issue, Griffith has urged the FCA to prioritise its upcoming review of PEP rules over other initiatives.

PEP Screening Technology

The risk, effort, and expense involved in PEP screening plays a significant part in financial institutions’ compliance decisions about high-profile customers. Banks that cannot or do not want to take on unacceptable levels of risk may opt to refuse services (or close accounts) as an alternative to shouldering a costly compliance burden, in a process known as “de-risking” or “de-banking”. These decisions may lead to negative outcomes, including reputational damage for the banks, as customers are left with no way to access financial services.

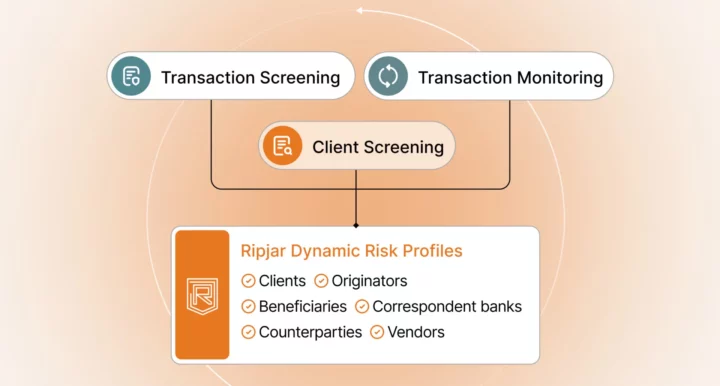

Effective PEP screening is a challenge, but financial institutions can make the process easier by leveraging technology, including integrating screening tools that can help them determine PEP status and true customer risk faster and more accurately than ever. Ripjar’s Labyrinth Screening platform was designed for exactly that purpose, offering fast, flexible PEP screening, and facilitating customer name searches of global PEP lists that deliver actionable risk data in seconds.

Labyrinth adds meaningful depth and detail to name searches, incorporating thousands of adverse media sources in over 25 foreign languages. Powered by cutting-edge machine learning technology, Labyrinth also integrates AI Risk Profiles – an enhanced screening solution that enables firms to extract the most relevant risk data for a specific entity, minimising false positive alerts on similar-sounding names, and helping compliance teams make strong, informed decisions about their customers.

To find out more about how we can help you screen for PEP AML/CFT risk, get in touch today

Last updated: 6 January 2025