We live in a global society. The rapid changes in technology, infrastructure, and international business have meant that people are able to interact across the planet at a scale never before seen in history. The flow of goods and services around the world has become a vast interconnected web of commerce, allowing markets to operate seamlessly, competitively, across almost any border. Factories in China ship the latest smart phones to consumers in Chicago. Oil refined in Kuwait is turned into plastics and fuels for consumers in Kuala Lumpur. Gas from Siberia heats homes in Slovenia. In turn, these supply chains depend intimately on one another, making it virtually impossible to see where one begins and another ends.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only highlighted the fragility of this web. Like the fabled butterfly effect, restrictions at a factory in China, national stay-at-home orders, and curfews on international travel sends shockwaves all around the world; almost every industry has been significantly disrupted in one way or another. For instance, the dramatic rise in home working and home entertainment has been one factor in a global shortage of high-performance semiconductor chips, the kind found in laptops, game consoles and TVs. This in turn has led to huge production issues in disparate industries like car manufacturing where production lines and entire factories have even had to be shut down.

This complex web however has a darker side. Hidden within the legal and legitimate systems are vast networks of illicit networks of billions of pounds of trade, where criminals, terrorists and rogue states seek to take advantage for their own nefarious goals, which can come at immense cost to human safety, security and wellbeing. The pursuit of limitless cash fuels the worldwide trafficking perhaps as many as 50 million people into the horror of modern slavery. Black markets in exotic wildlife create billions in revenue while devastating our ecological habitats and vastly increases the risk of biological threats like viruses and pandemics.

These unconscionable acts sadly are highly profitable. Money, properly laundered, may fund lavish lifestyles of organised criminal gangs – fast cars, luxury travel and sprawling beachfront mansions. But money can buy more than jewellery, and other nefarious actors have used illicit finance and black market trade to further their own agenda of international terror, proliferation of nuclear weapons, and even to wage war itself.

At their height in 2014, the so-called Islamic State or ISIS which controlled swathes of Iraq and Syria were earning as much as $3 million per day from the sale of oil from the refineries of northern Iraq and Syria. ISIS used the funds and fuel for control and influence, allowing them to maintain a stranglehold on the people of the region, fuel for cars, trucks, factories and even hospitals, as well as to radicalise and recruit those to conduct deadly attacks on civilians in France, Germany, Egypt and the United Kingdom. Inevitably, oil from ISIS-controlled refineries and wells ended up throughout neighbouring countries via middle-men controlling old smuggling routes inherited from the Baathist era government (who used the routes to evade international sanctions) and Al Qeada. While allied air strikes eventually cut off most of this revenue, black market oil that directly funded terrorism would be readily available through places such as Turkey and Syria, who may haven even used state-owned companies to acquire and profit from this illicit resource.

War by other means

To combat these illicit networks and their corrosive effects, worldwide governments acting either independently or through shared governance and agreements in the EU and the United Nations have organised and communicated a series of international sanctions.

The use of such sanctions goes back at least as far as the ancient Greeks, blocking trade between nations could send a powerful political message and compel an adversary into changing their behaviour. But it was not until the 20th century that sanctions became institutionalised within the foreign policy toolkit. In the aftermath of World War I it was easy to think that sanctions (or even the threat of them) may be enough to deter states from another future conflict, but the on-set of World War 2 soon proved otherwise. More targeted efforts were needed and the modern system that focused on smart targeting of individuals and organisations was enshrined in the creation of the United Nations Security Council. Over time these were expanded, and influential governments such as the USA, UK and EU all developed their own lists of criminal and national security threats.

Modern sanction lists consist of highly specific and legally targeted entities – involved in everything from arms trafficking, nuclear proliferation, human trafficking, money laundering, terrorism, narcotics, and now even cyber attacks – which are consolidated and distributed to help organisations enforce them. Without enforcement they are meaningless lists, simply a summary of those who society collectively merely hopes would change in order to create a more peaceful and prosperous world.

Blocking these entities access to finance, energy, fuel, or other commodities is critical if they are to have any kind of coercive power to change. However, this is increasingly difficult, and we see three key challenges for managing the risk of these entities trading within global supply chains:

Complexity and Scale– the increasing complexity of global supply chains means that there is more chance for criminals to bypass control frameworks that are put in place. Companies operating at a global scale may have hundreds of thousands of counterparties involved in millions of transactions in many different jurisdictions. Understanding if any one of these suppliers, or a supplier of their suppliers are involved with an illegitimate entity can only occur with complete mastery of data.

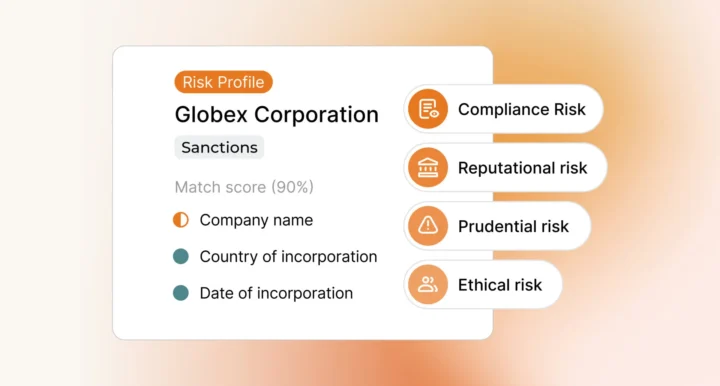

Counterparty Detection – Even with consistent data, matching whether a specific counterparty in a supply chain to a specific entity on a sanctions list can be difficult. Abu Sara Zahrani, a Saudi national based in Syria was a member of ISIS tasked with buying and selling its oil and commanding an entire division of 7 oilfields at their peak. Enforcing sanctions requires not only spotting his name but also any other permutations or variants, Faysal Ahmad Ali al-Zahrani, Abu Sarah al-Saudi or even فيصل احمد بن علي الزهراني. (for more, please see our blog on entity resolution).

Escalating Criminal Risk – Criminals go to great lengths to obfuscate and hide their illegitimate activities within legitimate trades and supply networks. This means sanction lists are often an incomplete view on risk. Data from other sources can help expand the understanding of risk, including that derived from news and open source intelligence (OSINT) to build up a more complete picture. (For more see our blog on exploiting open source news data).

Toward Artificial Intelligence Powered Enforcement

This blog has discussed the ways in which criminals and terrorist groups have exploited supply chains for their own gain and some of the challenges that global organisations have to enforce the international set of sanctions as laid out by the international community.

In order to overcome these challenges and to support leading companies to detect risks more effectively and efficiently within their complex and disparate supply chains, artificial intelligence and smart technologies are playing a significant role in ushering in a new generation of supply chain risk management.

Entity resolution technology developed by Ripjar uses millions of data points to derive more accurate search and matching logic than any other solution on the market. Compared to legacy solutions this reduces false positive matches by between 50-80% and increases accuracy and recall by 100%, meaning risks are more efficiently discovered and less time is consumed researching incorrect matches.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) also promises to expand our understanding of risk. This is a type of artificial intelligence that can read unstructured documents like news reports, documents or emails just like a human. We are using NLP to detect a far wider set of risks from open source news articles to augment watchlist-only matches and increase the ability for corporates to spot criminal activity.

Combined, these technology breakthroughs can scale to ensure that millions of transactions and counterparty dealings every day are screened, and help the teams tasked with preventing criminal abuse of resources, goods or services are able to conduct their investigations in a more efficient manner with overall more effective outcomes.

For more on our Supply Chain Screening Solution please click here: https://ripjar.com/client-screening/

Or download our whitepaper here: https://ripjar.com/resources/whitepapers/client-screening-next-generation-approach/

Last updated: 31 December 2024