The European Union’s Anti-Money Laundering Directives (AMLD) are issued periodically to adjust the bloc’s collective regulatory response to the threat of money laundering and terrorism financing. When the European Parliament hands down a new money laundering directive, EU member-states have an implementation period in which to transcribe the legislation into domestic law and ensure that all domestic banks and financial institutions are compliant.

Each AMLD broadly reflects changes to the global financial risk landscape, often requiring firms to expand anti-money laundering and counter-financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) measures to new types of service or customer or to adjust to new criminal methodologies. The most recent AMLD was the Sixth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (6AMLD) which was issued on 3 December 2020, with an implementation date of 3 June 2021. 6AMLD broadly strengthened measures introduced in 5AMLD, while adjusting other AML/CFT compliance measures to reflect changing criminal threats.

With 6AMLD now in legal effect in every EU member state, compliance officers should understand how their organization’s regulatory landscape has changed, and how to manage the new compliance responsibilities that it entails. Although it has left the EU and has opted not to implement 6AMLD, the UK has effectively already implemented the directive’s regulatory requirements in its domestic legislation. Similarly, EEA member states, such as Liechtenstein, or Switzerland (which is a member of the single market) must broadly implement the directive’s terms.

1. Regulatory Harmonization

6AMLD introduced a harmonized definition of the crime of money laundering to be used by each EU member state. The harmonization is intended to remove loopholes and inconsistencies in domestic legislation and address emerging money laundering methodologies that exploit new technologies or regulatory blindspots.

As part of the regulatory harmonization, the EU set out a list of 22 money laundering offences, including crimes such as tax evasion, insider trading, drug trafficking, and human trafficking. The list of 22 predicate offences included 2 new predicate offences: cybercrime and environmental crime, both of which reflect the EU’s desire to focus on emerging criminal threats and the shifting legislative focus of its member states.

2. Regulatory Scope

In addition to the new predicate offences, 6AMLD expanded the criminal definition of money laundering to include “aiding and abetting”. Accordingly, under 6AMLD, persons that help or enable money launderers to transform illegal money will also be considered guilty of the crime of money laundering – and be charged in the same way. Aiding and abetting takes in persons that attempt to launder money, or that encourage or incite others to launder money.

The expanded list of predicate offences and the expanded scope of the money laundering offence means that compliance officers should examine their own understanding of the law as it applies within their jurisdiction. Similarly, they should ensure that their internal AML programs are capable of capturing the new risk exposures that the adjusted definitions create.

3. Criminal Liability

6AMLD expanded the scope of criminal behaviour associated with money laundering but also changed the way that criminal liability applies to the offence. Prior to 6AMLD, only individual criminals could be held liable for money laundering offences: under the new regulations, criminal liability is extended to legal persons, which means that organizations can be punished for offences committed by the people that work for them. Organizations that are found guilty of money laundering face a range of penalties, including supervision orders or operational bans.

The change means that responsibility for corporate criminal conduct falls on management personnel in addition to individual employees. By expanding criminal liability, the EU is signaling that larger companies will be held to account under their regulatory regime and be expected to actively contribute to the global effort to combat financial crime.

4. Money Laundering Punishments

Under 6AMLD, the EU moved to address inconsistencies in money laundering punishments across member-states by increasing the minimum prison sentence for money laundering. Prior to the directive, the minimum prison sentence for individuals found guilty of money laundering was 1 year: under the new rules, the minimum sentence has increased to 4 years.

The increased sentences may not represent a significant change for many member states since they already mandate 4-year minimums (or longer) but will serve to bring outliers with lower sentences into alignment with the rest of the bloc. While it has not implemented 6AMLD, the UK’s money laundering punishments are harsh, with maximum prison terms of between 2 to 14 years depending on the severity of the crime for those found guilty of offences.

6AMLD’s sentencing changes also include discretion for judges to impose fines on individuals found guilty of money laundering and to prevent corporate entities found guilty of money laundering from accessing EU public funding programmes.

5. Dual Criminality

In another important step, 6AMLD has introduced changes to the way member states address dual criminality as it applies to the crime of money laundering. Dual criminality refers to crimes that span international borders – in the context of money laundering, it involves illegal funds that are laundered in a country other than the one in which they were acquired.

Under 6AMLD, member-states have specific information sharing and cooperation requirements to facilitate dual criminality money laundering prosecutions. In order to implement those changes effectively, some member-states may need to treat certain predicate offences as criminal offences regardless of whether they are illegal. These offences are:

- Involvement in organized crime

- Human trafficking and smuggling

- Sexual exploitation

- Drug trafficking

- Corruption

6AMLD also sets out guidance for authorities to determine where a dual-criminality money laundering prosecution should take place. That guidance suggests that member states should consider the location of the original victim of the predicate offence, the nationality of the offender, and where the money laundering offence took place.

Adapting to 6AMLD

Since it is now in effect, all banks and financial service providers in the EU must ensure that they are compliant with 6AMLD. In practice this means that compliance officers should review their internal compliance solutions to account for the adjustments to predicate offences and criminal liability. The following measures may be particularly important:

- Ensuring organization-wide understanding of 6AMLD’s new definition of money laundering and the 22 money laundering predicate offences.

- Reviewing criminal liability for potential money laundering offences, including the conduct of senior and management employees.

- Adjusting risk assessment procedures for alignment with the new risk landscape.

- Training compliance employees to meet their new obligations.

- Implementing suitable technology solutions to ensure ongoing compliance with 6AMLD.

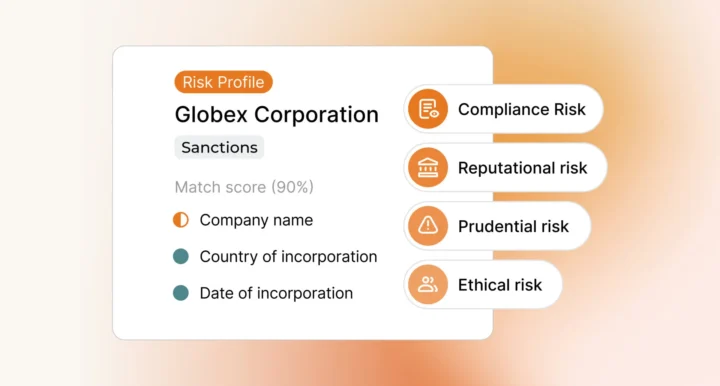

Screening obligations: 6AMLD’s expanded regulatory scope includes a requirement for firms to adjust their compliance screening solutions, including implementing enhanced customer due diligence for higher risk customers. In practice this means that firms must conduct “open source or adverse media searches” for occasional transactions and periodically throughout business relationships, in order to be aware of any emerging risk exposure.

GET IN TOUCH TO LEARN HOW RIPJAR CAN HELP YOU To Comply With 6AMLD

Last updated: 16 August 2024